Contrary to popular belief, job mobility programs aren’t for everyone. In fact, it’s really for just a small subset of your employee population, and it’s not who you think.

Everyone who wants job mobility, raise your hand.

Per a 2024 LinkedIn study on internal mobility, managers and leaders are twice as likely to move internally over individual contributors[1]. While the study doesn’t go into the reasons why that is the case, it can be surmised that at the manager and leadership level, the most common and valued skills revolve around strategic thinking, business acumen and people management; skills that are easily transferrable across functions or departments. Based on what we know from corporate America, we can also deduce that opportunities for managers and leaders are mostly based on openings in the hierarchy due to retirements, transfers, promotions, etc.

Ultimately, the candidates that fill those leadership openings are mostly pre-determined by executives and are rarely openly posted on job boards. This leads us to conclude that while managers and leaders may move the most, they represent a very small subset of the employee base and do not use or benefit from an internal mobility program.

HYPOTHESIS

| Job mobility programs are for early career, risk-taking individual contributors. |

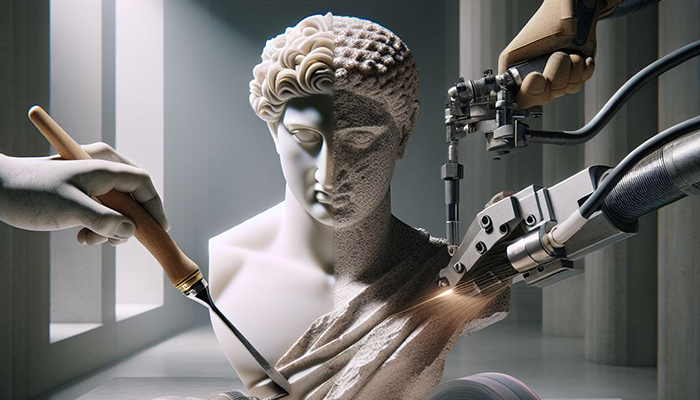

Chisel, Power tool, then Laser

By eliminating leaders and managers, we can narrow down the employee population that seeks mobility, to individual contributors.

Mobility is a Risk

Excluding those forced to abruptly change their careers, most individual contributors, specifically, mid and late-career employees will more than likely stay in their current roles rather than switch. This could be for any number of personal events that may be concurrently happening in their lives. For example, mid and late-career employees are likely to have dependents, such as children or elders, or may rely on dual incomes to make ends meet, i.e., housing or car payments, school loans, credit card debt, etc. Those in single income households, would even be less likely to risk their current source of income in exchange for trying something new.

Also, people in general are not attracted to change, and they are less so inclined later in life or after a significant amount of time has been invested in their career. It may be hard to have anyone admit it, but most established mid to late career individual contributors would probably rather “coast” in their current roles until retirement rather than start over in a new area.

Generations

Another way to look at this would be from a generational lens. Per a 2022 report, Gen Z and Millennials were more likely to ask for role changes compared with other generations (40% and 62% respectively)[2]. Generationally speaking, these two groups also represent the overwhelming majority of first-time job holders and early career employees. All of this suggests that the desire to transfer may be a temporal one, or until the employee “ages out” of the concern, thereby leaving early career employees as the likely principal consumers of job mobility programs.

Office vs. Front-Line

As mentioned, job mobility is an investment on behalf of the employer and the employee, and like all investments, they are subject to risk. Skill development for office-type work is generally available on-line, through a variety of vendors and options. Courseware catalogs are also very extensive and available in multiple-languages. Because of their online nature, these courses are more easily accessible during lunch hours, breaks or even from home. Most office workers are also salaried, which makes it easier for them to learn on the job, participate in conferences, etc. without an impact to pay.

Trade-type skills, however, typically require manual, or hands-on training requirements to demonstrate practical application. These trade schools or courses are normally offered during work-hours and therefore make it more challenging for front-line, hourly-paid workers to participate without company sponsorship or without sacrificing take-home pay. In addition, wage-based earners would also have to negotiate training time outside their work hours since there are overtime implications. So, while skill development for the front-line is possible, it is certainly more challenging when compared to office employees.

When combining this with our previous hypothesis, our audience mostly narrows down to highly self-motivated, early career, risk-taking, individual contributors (that lean towards office-based populations).

Early Career

If early career employees are the most likely to desire mobility, when would they seek it? By the large, a good portion of early career hires are sourced from intern programs. This provides students with the opportunity to discern their career choice as well as their potential first employer. Considering the cost of intern programs – interviewing, hiring, onboarding, training, mentoring and development, a company is making a significant investment in new hires. This means the better matched candidates are to their hired roles, the less likely they are to change paths, which in turn allows companies to best capitalize on their investment. In addition, some companies even offer rotational programs for early career employees, allowing them another opportunity to further refine their career path. Unless there is immediate “buyers regret”, new early career new hires would still need at least a couple of years to fairly assess whether they wish to remain in a role that was related to their field of study.

Let’s do a little pseudo-math here for giggles.

Retirement Age (65) - Starting Age (20) = 45 years (Employment Span)

Dividing it equally among early, mid and late careers: 15 years per stage

Now, let’s break down those 15 early career years into three stages:

Years 1-5: [Assessment]

- Will their first employer be their "forever employer"?

- Do expectations between their chosen field of study and their work role match?

- How does their work-life balance align to their desired lifestyle?

Years 6-10: [Action]

- Stay or leave based on whether they feel they have a future at their company

- Choose management or individual technical expert path

- Remain or choose a different line of work/profession

Years 11-15: [Acceptance]

- Company becomes top employer of choice for future retirement

- Promotions are actively sought or they seek recognition in their technical area

- Make peace with career area/lifestyle choice as they approach mid-career stage

Of these three stages, it’s very possible that the five years in the “Action” stage is where job mobility desires are likely to peak. So if you apply this to your company’s demographics and then further refine it by multiplying the percentage of high-performers you have, that’s essentially your key audience.

Granted, this doesn’t go into how many roles are mission/operation critical or what the cost per employee would be to have a mobility program. In our final section, let’s jump into what companies should consider, in addition to cost, as they develop their internal programs.

[1] Internal Mobility is Booming – But Not for Everybody, LinkedIn, G. Lewis, February 2024

[2] 2022 Great Resignation: The State of Internal Mobility and Employee Retention Report, Lever, 2022